Having grown up in Norway, my father was surrounded by fjords teaming with fish. In

his youth, he often supplied the dinner table with his catches. I remember his stories

about battling giant codfish and salmon with envy as I could only dream of having such

experiences as a fisherman.

These days, my fishing is more a state of mind than it is a

sure thing, but it has taught me that one must be a tireless optimist and persistent in order

to succeed. This approach may have carried over into how I work as a metal sculptor.

I have been designing and fabricating lighting, sculpture and furniture for the past 12

years. I have learned much on the job, with each new project a leap of faith for me, and

at times, for the client. Over time, I became more comfortable with the concept of not

knowing exactly how I was going to design or build something. This fear of not having

all the answers evolved into an energizing force, exciting me with enthusiasm and

optimism, driving me headfirst into the project. Persuading steel into elegant forms is a

process that requires a positive outlook and a lot of persistence as the path to completion

is not always road mapped and there are many dead ends along the way.

I have been designing and fabricating lighting, sculpture and furniture for the past 12

years. I have learned much on the job, with each new project a leap of faith for me, and

at times, for the client. Over time, I became more comfortable with the concept of not

knowing exactly how I was going to design or build something. This fear of not having

all the answers evolved into an energizing force, exciting me with enthusiasm and

optimism, driving me headfirst into the project. Persuading steel into elegant forms is a

process that requires a positive outlook and a lot of persistence as the path to completion

is not always road mapped and there are many dead ends along the way.

Most of my projects are smaller than 20 feet in length and weigh less than 1000 pounds,

which I can handle, solo. As a sole proprietor, I wear a lot of hats, from salesman and

designer, to shop foreman and installer I don’t have employees because half the time,

even I am not sure what I am going to do next, making it difficult to direct assistants. But

that all changed last summer when I landed the biggest job of my career.

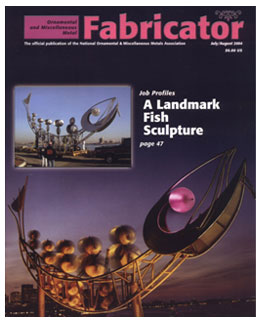

The owner of Legal Sea Foods Restaurants, a 30-location private restaurant chain,

approached me to design and build a sculpture for his new corporate headquarters and

distribution center in the Historic Seaport District on the Boston Harbor. I had completed

several projects for him over the past 6 years including a couple of 12-foot tall abstract

fish sculptures, custom lighting, and two water features. He wanted a landmark sculpture

that people could see from miles away in the harbor, even from planes landing at Logan

International Airport on the other side of the harbor. Oh yes, and it also should be wind

interactive to take advantage of the persistent winds that frequent the harbor. I was very

excited and a little terrified; this was a very big challenge requiring solving both

mechanical and aesthetic problems, something I would need a lot of help with. But first I

had some problem solving to do.

Over the next several weeks, I discovered that Boston is one of the windiest cities in the

country. I researched the wind power industry to see the various types of wind turbine

designs that I might incorporate into the piece, reviewed how other artists had made wind

interactive sculptures, and dug through old patent drawings. I decided against using

aerodynamic lift propeller type blades because of their high top-end rotational speeds

with the potential to exceed 600 miles per hour as I was not making a giant blender. I

wanted to use something less efficient, more peaceful, preferably something from

yesterday’s technology. Then I found it: the Savonius rotor which drags along at a

rotational speed of less than the acting wind speed; a rotor, with a history spanning

thousands of years, from the early grain mill motors in the deserts of the Middle East to

the water pump of today’s Australian farmers, seemed ideal, all I have to do is adapt it to

my needs.

The next question was what kind of fish should I depict? Should I use my favorites?

Salmon? Tuna? Bass? More research led me to a book titled, “Cod, Biography of the fish

that changed the World,” by Mark Kurlansky. It chronicled the importance of codfish, the

one species, which fueled the economy of New England and was responsible for the early

development of Boston and its working waterfront. I thought an abstract cod fish

sculpture would be an appropriate landmark for the client and the historic seaport district

neighborhood.

Thinking about the design possibilities, I realized the sculpture’s prime audience is the

many boaters who navigate the harbor. Commuter boats and recreational sailors would

see this sculpture perched 40 feet above the water’s edge, and I began to think of ways to

involve them. I proposed that the eye would somehow signal the wind speed in color,

connecting the fish to its environment. I wanted to use architectural wash LED color

panels to do the signaling but would have to find an electrical engineer to help me build

the brain to control it, something I had to trust I would find.

I decided the sculpture would be 45-feet long, made in three major sections for ease of

transport with the largest part able to fit easily through the 10 foot by 10 foot rollup door

of the shop. I still had to solve what it would look like.

I filled pages with cod-like fish sketches and tried to distill them down into a simple

abstraction. Most of my designs had the rotors on vertical shafts supported by the outline

of the fish top and bottom and I wasn’t liking what I was seeing. Something my wife

had volunteered kept coming to mind. She wanted to see the rotors almost floating with

little visible means of support, something I initially thought was impossible but a few

more versions, and I felt I was on to something which just might work.

I made a 1-inch scale drawing and then a scale model in steel. Once fleshed out in the

third dimension, I could see how the frame could act as a stiff support to cantilever the

rotors high above the frame. I also saw some unexpected things. The curved belly had a

ship’s hull shape and the rotors almost had a sail-like configuration, evoking elements of

a Viking ship or sailing schooner that was unplanned, yet somehow appropriate.

My client approved the design and released me to start fabrication and I prepared the

shop for the materials and the work to take place. I hired a strong hand to move out all

non essential tools and materials and help bring in the first loads of stainless steel pipe

and sheet and to assist me in the pipe bending. By now I had data back from the two

engineers I hired to specify the shaft diameters and sign off on the structure of the fish

and its attachment to the building.

We laid out the curves at full scale on the floor in preparation for bending. After a lot of

head scratching, we started with the main frame nearest the tail so that the tail section,

when completed could be test fitted while flat on the floor instead of standing 30 feet in

the rafters. The sculpture could only be fully assembled at the site because it would be

too large for transport so I had to be careful to assure that the parts would all fit together

without ever seeing it together in the shop, now that was an act of faith. The arching body

pipes were schedule 40 3 –1/2” pipe with an OD of 4-inches, weighing about 9 pounds a

foot. We incrementally bent eight 20-foot lengths over the next 3 weeks, one inch at a

time, with some pipe sections requiring over 250 hydraulic bends to complete. The tail

section was completed next and test fitted into the rear, lower part of the fish and put

aside. We continued to build the lower chords and combine them in a ladder arrangement

by cutting 18” straight pieces and mitering them to accept the 3-1/2” pipe. I hired a full

time welder so I could focus on the miter cutting. I had no idea how much work was in

the miters. 12 vertical pieces had to be mitered to fit between the upper and the lower

chords of the frame at set locations complicated by the fact that the pipes were not

parallel or in line. Two weeks of miter cutting consisted of plasma cutting, grinding and

test fitting, templating, and then more cutting, grinding and test fitting until it fit snuggly

together.

The manner in which the fish eye was going to communicate wind speed consumed my

thoughts for weeks. I needed to somehow translate the wind speed into color. A sailor

friend mentioned the Beaufort Wind Strength Scale, which is a numerical scale, invented

in 1805 to describe wind strength based on visual cues. And because it is familiar to most

sailors today, I thought it was fitting. I could program the eye to flash the number of the

force, such that three pulses equaled Beaufort Scale 3 (7-12 mph). I hoped the pulsing

eye would generate curiosity and over time people would learn what it conveyed via

visits to the Legal Sea Foods website, where they could see the Beaufort scale and the

fish sculpture in live motion on the web camera.

The fish needed a brain to control the pulsing colors of the eye, so I inquired around

Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, and quizzed the LED manufacturer

and anyone I could think of. I asked the firm that sold me the anemometer that I used to

test wind speeds at the site, and they just happened to know an engineer who would be

willing and able to meet the challenge. I sent him off to develop the wind to eye interface

circuitry and program.

I had ordered custom stainless steel bearings and precision ground hollow shafting for the

rotor assemblies. I had the 30 inch diameter eyeball fabricated and all the LED panels and

data/power supplies and hardware shipped. I also ordered the web camera and housing

for the fish and harbor viewing via the internet, an idea suggested by my client.

The site was prepared with amber lighting to cast a golden glow on the fish at night. I

sited the webcam and housing on the roof and scheduled a crane company to transport the

parts to the site for assembly.

I was getting more nervous as the delivery and assembly dates arrived. Everything had to

fit together and work on the first try. Four months of fabrication and I still hadn’t seen it

assembled as one complete 45-foot long piece. The delivery day was a very gusty and

rainy, raw autumn day. We unceremoniously crawled through Boston’s crowded streets

making 5 trips in over 7 hours to the site 4 miles away. Now I was worried about the next

day’s weather and how I was going to assemble and weld everything together in driving

rain, I could only be optimistic and hope for the best.

The next day was the most bucolic day one could hope for; it was bright, warm and calm.

We welded the tail section to the frame while on the ground then hoisted the assembly to

the stand on the flatbed trailer and attached the head on the first try. The owner’s

representative, Lynette, said I cracked my first smile that day. My fears were slowly

subsiding. The rotor assemblies were bolted to the frame while the local papers arrived

for photos. The late day amber sun reflected off the completed sculpture for the first time.

I heard that I smiled again.

Halloween day, we backed the 2800-pound sculpture to the crane awaiting final lifting

and welding into place 40 feet up overlooking the harbor. Another unusually beautiful

day with no winds and warm temperatures added to the smooth installation. By

lunchtime, champagne was flowing, and we had a dedication party on the roof with the

company top brass and media attending. I felt like a proud sportsman with his trophy

catch. The fish that fought me tooth and nail was won. Now, if only I could land a keeper

striped bass. |